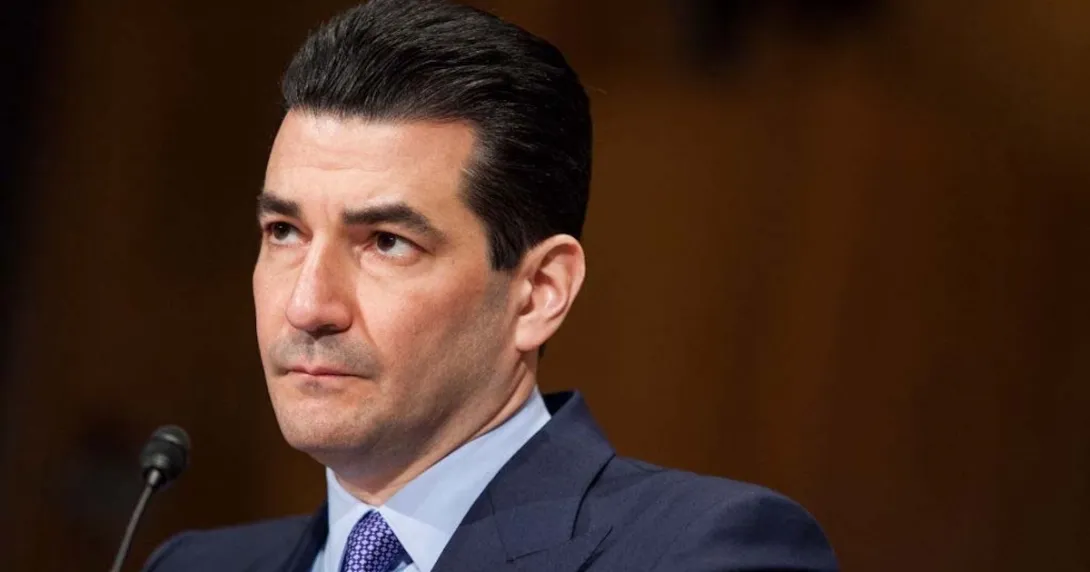

Photo: Zach Gibson/Getty Images

At The Constellation Forum 2025 sponsored by Northwell Health that was held Oct. 22-23 in New York, former FDA Commissioner Dr. Scott Gottlieb discussed ways government policy can help promote bioelectronic medicine innovation.

Gottlieb said that while the FDA has been trying to lean forward in this space and while it holds tremendous promise, there are regulatory challenges for the agency.

"The FDA has been historically pretty adept at evaluating hardware," Gottlieb said.

"For example, the issues around brain computer interfaces, how those devices get implanted, their ability and what the long-term potential risks are, making sure that it has structural integrity."

Gottlieb said the FDA went through a period back in the 2000s where the agency had challenges with cardiovascular devices, things like electrical probes that were put into the heart where the engineering was not sufficient to ensure the long-term success of the tools.

"I think the FDA has gotten much more adept at assessing the physical components of these kinds of devices and certainly has a lot of experience with vagal nerve stimulations and hardware like that," Gottlieb said.

Gottlieb asserted that the bigger challenge will be on the software side.

"If you think about a brain computer interface, a lot of the innovation is going to be not within just the hardware itself but the interface – the tools, the software, the AI devices being used to do the interpretive analysis and help direct the energy into the brain to yield the clinical outcome that you are seeking," Gottlieb said.

He said the challenge for the agency is that the regulatory paradigm is one of approving products where the development timeline has a defined start and finish, but when one thinks about the software tools that enable some of these devices, the timeline is more dynamic.

"They need to be constantly upgraded over time. Their learning systems are not just going to learn on the collected experience in the software and data that they are trained on, but also on the patient's data. You want tools that can adapt to the unique characteristics of patients. That is what is ultimately going to make them perform very well," Gottlieb said.

"The tools that the agency is forced to work with because of the legal structure that it has, the sort of 510(k)/PMA [Premarket Approval] process, did not contemplate this. That statute was written back in the 1970s when no one envisioned the kinds of technologies that would be available today."

Gottlieb said that during his time at the FDA, the agency piloted a program called Pre-Cert that was put into legislation but was never passed.

"What it was, was a firm-based approach to regulation where we said if you demonstrate that you do really good validation with your software tools, you can come to market with iterative changes and sort of real-time adaptations without having to come into the agency and file a new supplement or generate data that you have to report to your own file in case the agency audits you downstream and it worked well," he said.

The concept for the approach came about when Apple approached the FDA seeking the first approval for its Apple Watch.

"A lot of people did not think we would be able to approve the Apple Watch as a health device because they figured the FDA would do what it always does, which is rip apart the watch and try to figure out the hardware, and it would be hopelessly complex and we just wouldn't be able to figure out how to get it approved and get out of our own way, if you will," Gottlieb said.

He said that when Apple came into the agency to show the validation work it did, which he said was extensive, the FDA asked, "Why are we looking at the device? Why don't we focus on the validation and their ability to continue to do that validation as they come to market with new adaptations to the hardware"?

"We basically approved it on the premise of this firm-based approach to regulation. Instead of regulating the device, we will regulate the firm and regulate their ability to do good validation and then they could come to market with iterative changes," Gottlieb said.

"That is how the concept was first formed, and I think it is ultimately the paradigm that we are going to need to adopt within this context."

Gottlieb addressed the issue of what the FDA could do to expedite or accelerate trials for innovative technologies.

"A lot of the challenge right now on both the drug and the device side, and it is a little bit more acute on the drug side and a little bit easier to see this on the drug side because it is playing out in real time in the venture community and the early biotech communities, is just getting into clinical trials at the outset," Gottlieb said.

He said the level of pre-clinical toxicology work that the agency requires on the drug side or pre-clinical testing in animal models on the device side is exhaustive and expensive.

According to Gottlieb, the Chinese government sponsored studies at centers that have a lot of expertise doing those studies.

He said they trust the center to have a strong institutional review board (IRB) in place and perform good validation work as well as make sure they have appropriate guardrails in place to protect patients.

"You allow a little bit more of a decentralized, early clinical development. It also allows innovators who have come out of academic institutions to advance products a little bit further and capture more of the value from those products before they end up licensing them to a larger company," Gottlieb said.

He said this could be a good revenue stream and a good source of capital for academic centers that want to take their products further down the innovation chain; however, he noted that this has been a big impediment, which has caused many companies to take their products to China and Australia to get early human data and then bring that data back to the U.S.

"I still think the U.S. is going to be the place where you want to do, with the PMA trials, the large phase 3 clinical studies to demonstrate safety and effectiveness to try to bring a product to the market. I still think we are best-in-class. It is a competitive advantage in getting the certainty that we get around products before they come to market," Gottlieb said.

For early development, however, Gottlieb said the U.S. is being outcompeted.

"I think there is a lot they could do to reform that; it has not been a focus of the FDA right now. If you want to fashion a deliberate campaign to try and make us more competitive with China, that is where I would look first," Gottlieb said.